Earlier this month, foreign ministers convened in Paris in an attempt to kick-start the moribund Israeli–Palestinian peace process. And as the Obama presidency winds up, many predict the US President will outline parameters of a future peace agreement, possibly as part of a UN Security Council resolution.

Perhaps to ward off these events (and dispel signs of inaction), Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu last week dragged up the ghost of the Arab Peace Initiative.

And so it goes. Despite the Middle East’s many pressing issues—turmoil in Syria, Libya and Yemen, the growing Saudi–Iranian sectarian cold war—Western powers return again and again to the prospect of Israeli–Palestinian peace.

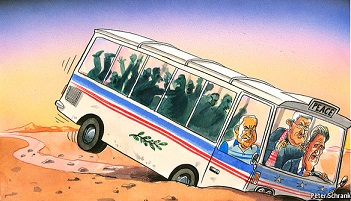

Asking why is important. But we might also ask why the peace they so desperately crave eludes them. For almost a century the League of Nations, the United Nations, the British, the US, the Norwegians, the French, the Arab League and a host of Israelis and Palestinians have nominated themselves as having come up with a solution. None have worked.

It has been 23 years since the first Israeli–Palestinian peace agreement. The Oslo process was supposed to usher in a ‘New Middle East’. Instead, thousands of Israelis and Palestinians have since been killed. Indeed, more Israelis died as a result of terrorism during the seven years of the Oslo process than in any preceding seven-year period. (Though this number was dwarfed by the number of Israelis killed in the seven years from September 2000.)

Why is the Israeli–Palestinian dispute so resistant to resolution? The answer isn’t as simple as pointing to the traditional ‘obstacles to peace’, such as settlements or terrorism. These are but symptoms. To understand the problem, we need to take a step back—to look at the forest instead of focusing on the trees.

What is frequently called the ‘Israeli–Palestinian conflict’ actually consists of multiple, interwoven conflicts. To understand why the over-arching dispute hasn’t been resolved we need to identify these individual conflicts. This is accomplished by examining the objectives of all the parties involved. By doing so, we can distil two main types of conflict—territorial and existential.

Territorial conflicts are fought over land or resources. If two states or national movements claim the same territory, they are in a territorial conflict. Resolution comes when they agree to share or divide the land between them. Most people view the Israeli–Palestinian dispute as a territorial conflict. But if this were the only conflict at play, there would have been peace decades ago.

Existential conflicts don’t necessary last forever—the wider Arab–Israel dispute was existential in nature until the Arab world and, later, the pragmatic Palestinian leadership, concluded they could not defeat Israel militarily and so softened their existential conflict into a territorial one. Realistically, though, there is little hope that Hamas and its ilk will give up their religiously-inspired existential conflict.

Since existential conflicts cannot be resolved, they must be won or managed. This means that before or during a territorialist peace process, observers and participants must be aware that existentialist parties exist, that the prospect of peace enrages them and that they will violently seek to undermine that peace (because the compromises associated with territorialist peace weaken their visions of total victory).

For a territorialist outcome to be possible, territorialist leaders must not only be aware of the existence of existentialists, but also willing and able to force existentialists to accept territorialist will. This is a politically-difficult and sometimes bloody path to tread.

A significant obstacle is that the Palestinian leadership and media apparatus continue using existentialist themes—‘all of Israel is Palestine’; ‘right of return’—in their messaging. This indicates either they remain existentialist or do not have the courage to change the minds of the Palestinian people, who have been fed a diet of existentialist promises since the beginning of the dispute.

If the West wants peace, it must insist that the Palestinian Authority not only tackles the existentialists in its midst, but also presents itself as a true, territorialist alternative.

Unfortunately, the requisite awareness, willingness and ability do not currently exist, either internationally or locally. Until this is reversed, peacemaking is destined to remain an exercise in futility.

Bren Carlill will be speaking on this topic at Limmud Oz on 27 June. He blogs at www.themiddleeastexplained.com.

This article originally appeared in the Australian Jewish News.