After all, as one of four personal secretaries to Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler’s propaganda minister, Pomsel admitted to massaging down the numbers of German soldiers killed in battle, and rounding up the number of rapes committed by the Red Army.

Yet Pomsel, aged 31 and an experienced stenographer when she went to work for Goebbels in 1942, denied knowing anything about the holocaust until 1950, when she was freed from the Russian-run Buchenwald prison camp.

“I was a stupid and politically disinterested nobody from a simple background,” she claimed, during 30 hours of interviews from her Munich nursing home in 2013.

Originally recorded for a documentary, Pomsel’s 235 pages of testimony form the basis for Christopher Hampton’s play, premiering in Australia at Adelaide Festival, which invites us to debate how much Pomsel really knew.

But the play also asks us a more powerfully troubling question: in Pomsel’s position, would we have just gone along with things too?

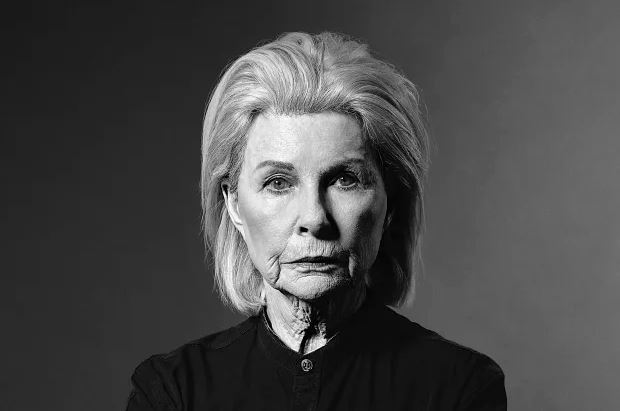

Robyn Nevin was in 1959 among the very first intake to NIDA, Australia’s national drama school, and her experience shines in a masterful performance as Pomsel here.

The set is a simple, impersonally furnished nursing home room, and after a while it ’s as if one is sitting there with the centenarian herself. Only the occasional cello interlude from Catherine Finnis, or haunting period newsreel images projected on to the walls, broke the spell of Nevin’s monologue.

Read the review by Michael Bailey in the Financial Review.