Elizabeth Holtzman was the youngest member of the US congress in 1973 when she was told by a lowly whistleblower working in immigration that her government not only knew Nazi collaborators were living in the US but had a long list of the unaccountably protected men and women – “useful enemies”, they were called.

She was appalled. Indeed, she could barely believe it. Soon after, Holtzman attended a budget session of the Immigration and Naturalisation Services department to ask its commissioner if such a list existed. He said it did. She asked to see it and was given 59 dossiers on brutal concentration camp overseers, cruel guards, who had tortured and killed women and children, and even gas chamber operators.

There were thousands of such barbarians calling America home. They may not have been the architects of the Final Solution but they were its loyal foot soldiers without whom there could have been no Holocaust.

Holtzman’s Office of Special Litigation Unit swung into action as the world marked the 40th anniversary of Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939.

Justice Department lawyer Allan Ryan was put in charge and by 1979 the era of organised Nazi hunting was under way. And it would change lives. The first it changed was Soviet-born Treblinka camp worker Fyodor Federenko. He was an enthusiastic killer of Jews, whom he liked to humiliate in their final moments – like making them crawl naked around the camp. He had tricked his way into the US under the Displaced Persons Act, become a US citizen in 1970, spent decades in a Philadelphia metal factory and retired to Florida.

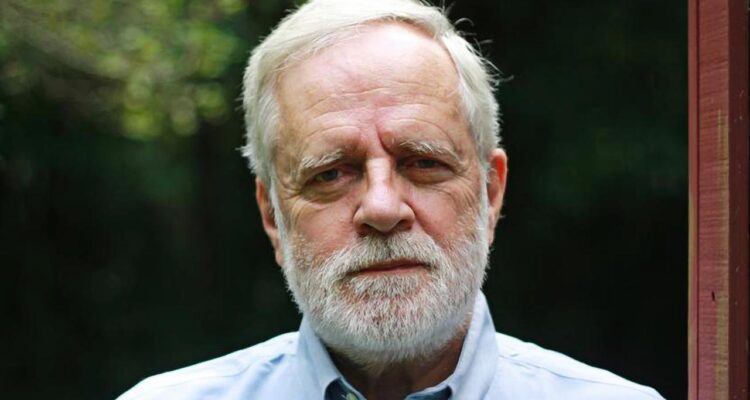

Read the obituary of Allan Andrew Ryan by Alan Howe.