The banality of evil has a new face. The West is so far advanced down the path of cultural relativism that its political leaders do not respond when Islamic leaders suggest killing homosexual people is acceptable if decreed by a committee. We have seen this all before. It was called Nazism.

The banality of evil was a phrase coined by political theorist Hannah Arendt to describe the methodical, bureaucratic nature of the Nazi killing machine.

After watching the trial of Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem and analysing reams of Third Reich documentation, Arendt concluded that the motive force of genocide was not the embodiment of the charismatic psychopath, as popular belief would have it. The Nazi genocide was accompanied by a gradual drift to mass conformity by individuals who ceded their individual will to the general will of the regime codified in the totalitarian state. Many were rewarded professionally by their degree of conformity to the rules of the Nazi regime.

The Holocaust was sustained by such systemic self-deception among Nazi leaders that the high command was buoyed by a sense of moral virtue even as it organised the mass murder of millions of innocents.

The Nazi genocide began, as do all genocidal wars, with the deliberate manipulation of language.

The first gas chambers were built in 1939 and grew out of Hitler’s euthanasia program that targeted the mentally ill deemed undesirable by the regime. Arendt records that between 1939 and 1941, about 50,000 Germans were gassed in what Nazis described as a humane program of “granting people a mercy death”. Hitler replaced the word “murder” with “mercy”, thereby expurgating guilt in advance and perverting the meaning of virtue so that the killing of citizens deemed undesirable by the regime was transformed into an act of compassion.

Compassionate death for undesirables. After a century marked by crimes against humanity so horrific they required a new lexicon, we should be alert to the language that announces the spirit of genocide moving through a nation.

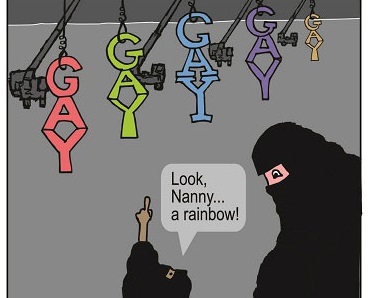

Yet in the days following the Orlando jihadist attack that claimed 49 lives at a gay nightclub, it emerged a sheik who preached death for gays was on a speaking tour in Australia. Sheik Farrokh Sekaleshfar stated in 2013: “Death is the sentence. There’s nothing to be embarrassed about this. Death is the sentence. We have to have that compassion for people. With homosexuals, it’s the same. Out of compassion, let’s get rid of them now.”

When pressed about his hate speech last week, the sheik protested he had been quoted out of context. So what is the context in which killing gays is deemed acceptable according to Sekaleshfar? Islam. In an interview with The Australian’s Simon King, he said: “In Islam this is the ruling … by killing him he will no longer sin and therefore we are saving him in the hereafter, that’s what I mean by it’s the compassionate thing to do.” He urged Muslims not to feel embarrassed about “the law according to Islam”.

The public outcry was so fierce that the sheik left the country, but we are yet to learn if politicians have ensured he will never return. As though the week had not yielded enough murdered gay men to satiate hate sheiks, we learnt that the leadership of the Australian National Imams Council includes at least three executives who believe homosexuality should be punished by death. Their justification for such barbarity? Islamic law.

Speaking to The Weekend Australian, the chairman of the Council of Imams Queensland, Imam Yusuf Peer, defended capital punishment for homosexuals because “this is what the sharia law says and we have to follow that”. And then he uttered a sentence that chilled my blood: “Nobody can implement Islamic sharia on their own. There is a procedure, there is arbitration, there is a committee.”

There is the banality of evil.

As a child, I had an unusual preoccupation with trying to decipher the animus of the Holocaust. I pored through books to uncover a single trigger, to capture a solitary truth — a concrete precedent to wield like a weapon against the darkness should it ever return. But I didn’t believe it would in our lifetime.

The banality of evil is a creeping nightmare; the gradual dilation of totalitarian thought in high places; the supersession of moral virtue by the orderly administration of misanthropy. It is Jews marched onto trains destined for camps where they will be forced to dig each other’s graves. It is the tiny body of a Christian toddler held aloft by her wailing father after being decapitated by Islamic State. It is the pink triangle sewn stitch-by-stitch onto the shirt of a man who is marked for murder simply because he loved — and was loved in return.

There was no single cause of the Holocaust, no pivotal moment in which the fate of millions was surrendered to the darkest forces of humanity. The truth is much worse. There were years of political deals between governments, scores of ominous warnings and innumerable propaganda methods designed by the Nazi regime to stir the hatred of the masses and solicit their acquiescence to the murder of fellow citizens the regime deemed undesirable. There is no final solution to the Final Solution.

When I realised that truth as a child, I made a small promise to myself. It was simply this: I will never be a person who just watches the trains go by. The notion that killing gays is acceptable if determined by a sharia committee should shock the nation into action. We must not accept the creeping banality of evil.

This article by Jennifer Oriel appeared in The Australian