Israel will go to the polls for the third time in less than a year. What makes it so hard for a clear winner to emerge?

Israel has often been called the only democracy in the Middle East. This is not quite true.

The Economist’s Global Democracy Index for 2019, which ranks 167 countries by five democratic criteria, lists Israel as a “flawed democracy”.* Israel scores well on electoral process/pluralism and political participation, but is marked down on government functioning, political culture, and, in particular, civil liberties, where, Israel scores just 5.88 out of a possible 10.

These failings bring Israel down to 28th on the list, but that’s still much higher than any of its neighbours. The next is Tunisia, likewise a “flawed democracy” at 53rd, with the remainder listed as “hybrid regimes” (nations with regular electoral frauds and other systemic failings) or “authoritarian”.

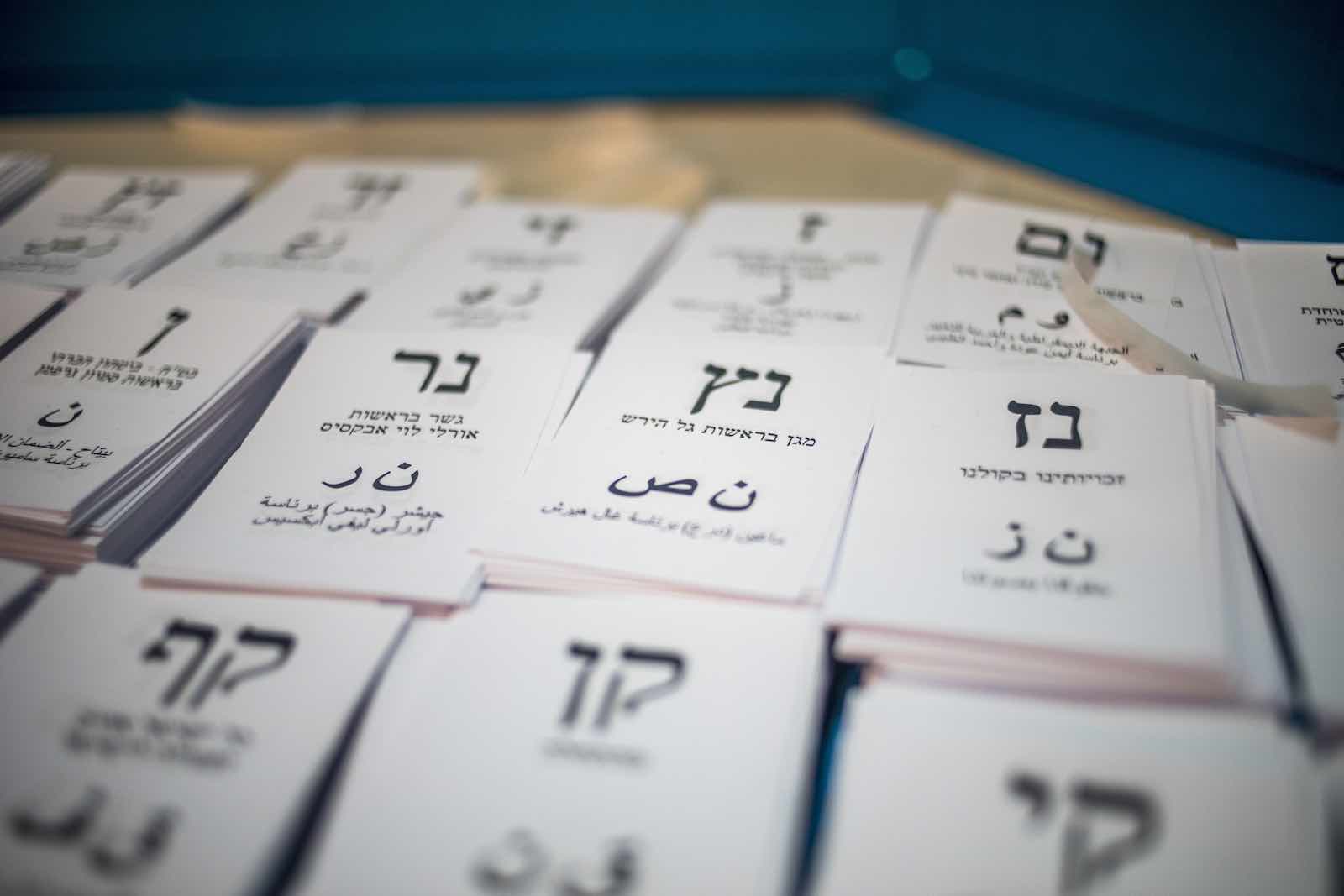

Against this background, Israel’s system of choosing political representatives is certainly the most democratic in the region. In particular, its procedures and outcomes are underpinned by strong democratic institutions.

Elections are overseen by the Central Elections Committee (CEC), comprising representatives of party groupings within the Knesset (parliament) and chaired by a judge of the Israeli Supreme Court. This is less transparent than a non-partisan electoral commission as we have in Australia. But an important safeguard is provided in that CEC decisions can be appealed to the Israeli Supreme court.

Read the article by Ian Parmeter in The Interpreter.