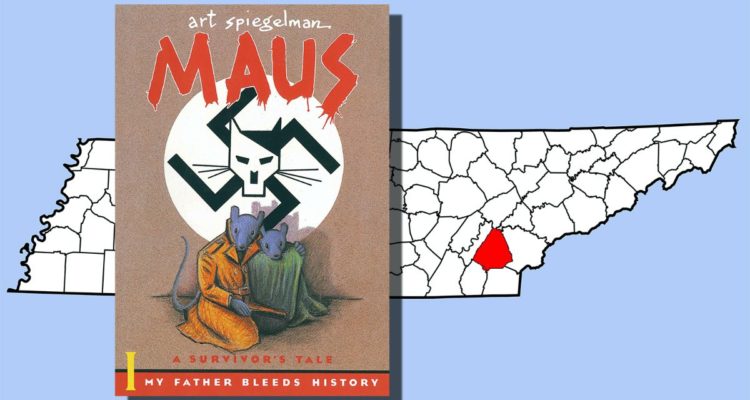

Last month, a school district in Tennessee voted to remove from its reading lists the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman, which imaginatively retells the story of the author’s Jewish parents, particularly the father’s experiences as a Holocaust survivor, through a fictionalised tale of a family of mice persecuted by cats.

Such material – a reflection of actual events that happened to actual people – is indeed heavy reading for adults, let alone for young people. It’s a story we would wish never needed to be told. But these stories did happen and do happen.

The decision of when it is appropriate for children to face such truths about our world is not an easy one, and differs from child to child. One of the great gifts of good literature is that it allows us to learn about the world, both its goodness and its lack of goodness, in ways we could never experience for ourselves.

However, the horror of this real-life story isn’t the reason Maus was removed from McMinn County’s school curriculum. Rather, the school board removed it because of an illustration of a nude character and the book’s “inappropriate language.”

It might be one of the more puzzling challenges to books in schools, of which it is only the latest: The American Library Association reported that “273 books were affected by censorship attempts” in 2020 alone.

It’s important to note that books are selected and unselected for library shelves and schools curriculums all the time, and not selecting one book or another is not necessarily censorship. Nor is updating a curriculum by replacing lesser books with better ones censorship.

Read the article by Karen Swallow Prior in Sight Magazine.