Wherever you go, there you are. It is one of the truisms of travel: that you bring more than just physical baggage with you. But Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman magnifies the idea in his deceptively winsome comedy It Must Be Heaven. Wherever he goes, Suleiman – who plays himself, albeit more flummoxed by the world than he seems to be in real life – finds himself in a version of Palestine.

Helicopters whirr overhead in New York; ordinary citizens are inexplicably armed to the teeth in Paris; nothing seems to make sense anywhere. “My feeling is that the Palestinians might be one of the most oppressed and occupied peoples in the world today, but I can also say that unfortunately there are many layers and levels of occupations,” he says. “Not only military, but also economic and psychological (ones).”

Similar tension and anxiety reign everywhere, he says. “Palestine becomes an elastic form of oppression.”

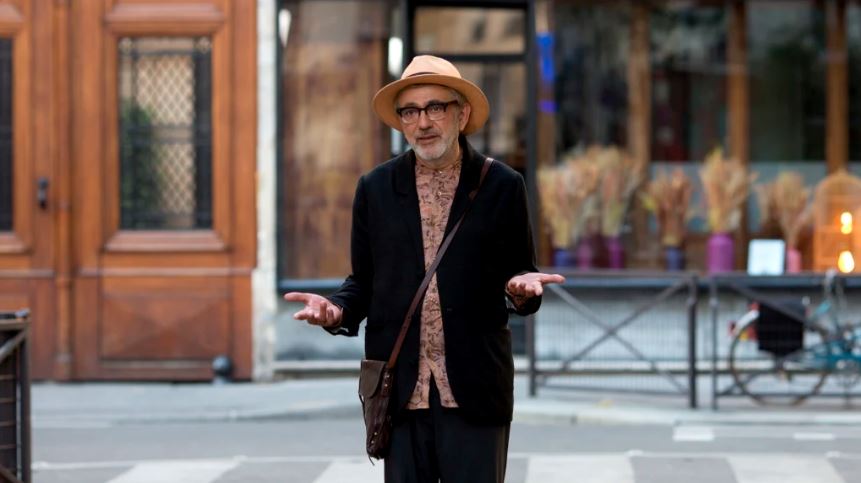

Suleiman is 60. His character on screen, established in his 2002 film Divine Intervention, hardly ever speaks. “This time I said ‘Nazareth’ when the taxi driver asks where I’m from, and, ‘I’m Palestinian’. They’re not even words. They’re codes,” he says. “I think that, as much as you can do with an image, why do you need words? It’s always a challenge to limit and censor information, but I cannot stand giving information in a film; I find that extremely boring. I prefer to leave things in the poetic. So I try to reduce as much as possible and let the cinema do what it can do.”

Read the article by Stephanie Bunbury in The Sydney Morning Herald.