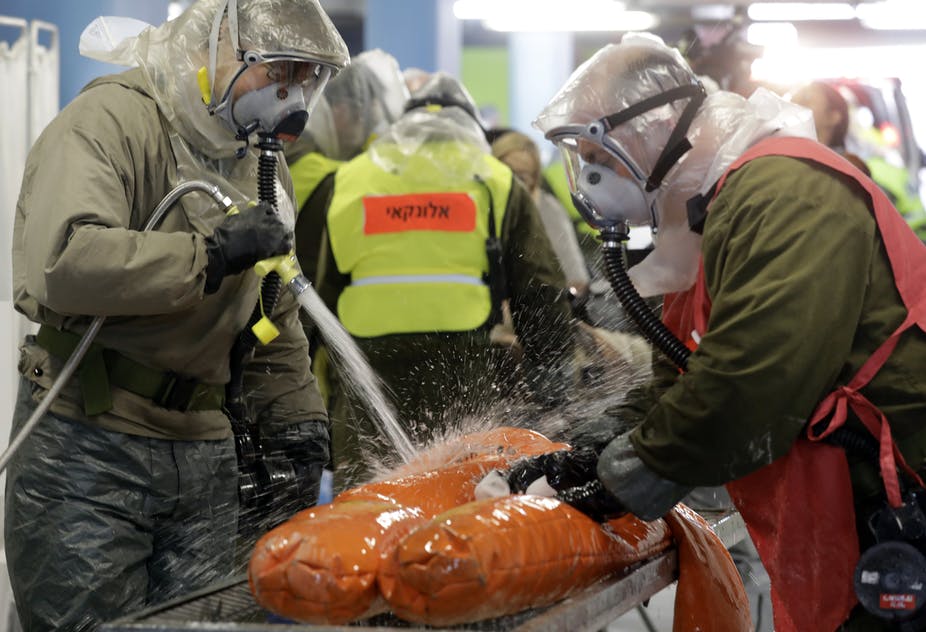

The multilateral attack on Bashar al-Assad’s chemical weapons facilities in Syria after a lethal gas attack in East Ghouta is already fading from memory, but the question it poses remains: how can the spread of chemical weapons across the Middle East be controlled? And answering that question demands scrutiny of the region’s most powerful and yet most opaque military power: Israel.

Israel’s chemical and biological weapons programme is shrouded in even greater secrecy than its notoriously opaque nuclear programme. Both the weapons and the secrecy around them are born of the same strategic imperative, namely to limit existential threats to the Israeli state.

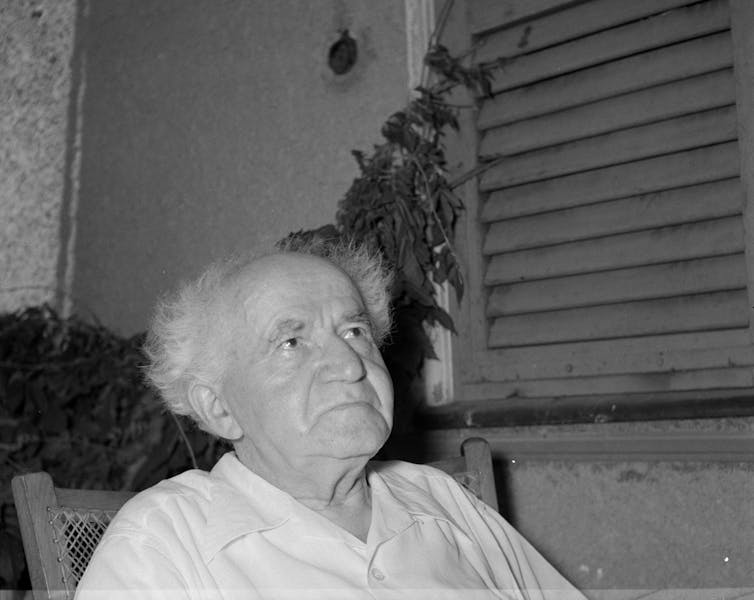

The programme was initiated under Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, who authorised it only reluctantly. Both he and subsequent leaders were wary of introducing such weapons into the Arab-Israeli conflict, fearing they might trigger a regional arms race. Nonetheless, even prior to the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Israel initiated research into unconventional warfare through the HEMED BEIT unit, forefather of the government-controlled Israel Institute for Biological Research (IIBR).

In 2013, after the last set of international efforts to rid Syria of chemical weapons, Foreign Policy magazine published a set of CIA documents from 1983 that revealed evidence Israel had pursued a chemical weapons programme. Suddenly, attention was again focused on the IIBR – long suspected of being the research centre behind the Israeli programme.

Now, one of the foremost experts on Israel’s nuclear policy and strategy, Professor Avner Cohen, has seized the opportunity to reiterate that Israel should ratify the Chemical Weapons Convention, which it signed in 1992. Since Israel has never put the treaty into effect, the exact nature of the weapons it has developed and possibly still possesses remains the subject of international speculation.

Self-defence and deterrence

As Cohen explains, the 1983 CIA documents likely evidence the remnant of a programme developed in the 1950s and 1960s. Around that time, Egypt developed chemical weapons and tested them during the Yemeni civil war. Anticipating Egypt’s plans as early as 1955, Ben Gurion soughtan “additional cheap non-conventional capability” that could be operationalised if hostilities with Egypt escalated. This capability was probably upgraded and maintained with assistance from France, whose Beni Ounif chemical weapons testing range in the Algerian Sahara was visited by Israeli scientists in the 1960s.

It seems the deterrent effect may have worked in the turbulent years that followed. Despite Israel’s preparations for chemical assault, experts have suggested that Egypt refrained from using chemical weapons against Israel in the 1967 Six Day War because Egypt “feared Israeli retaliation in-kind”.

Although Israel acceded to the 1925 Geneva Weapons Protocol on February 29, 1969, alongside other countries with chemical stockpiles at the time such as the US, Cohen writes that the contents of its arsenal were considered unsavoury but “legitimate retaliatory weapons”. Egypt long retained an advanced chemical weapons programme; it provided WMD to Syria in the early 1970s and technological assistance to Iraq in the late 70s and 80s. Saddam’s Iraq also threatened Israel with chemically armed ballistic missile attacks during the First Gulf War. In this climate, there was little incentive for Israel to forgo its chemical weapons capability.

While Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin tried to end Israel’s chemical ambiguity by signing the Chemical Weapons Convention, the geopolitical realities of the size of neighbouring chemical weapons arsenals meant the Israeli establishment still believed it needed an equivalent capacity to serve as a deterrent.

The general consensus today is that while there’s little evidence that Israel maintains a chemical weapons stockpile, it retains “breakout capacity” – that is, it could readily mobilise its significant scientific and technological knowledge to restart its programme.

A new world

Given its superiority in conventional weaponry and nuclear capability, it seems unlikely that Israel would deploy chemical weapons if it were attacked. However, as surrounding nations repeatedly cite this weapons capability as the reason they retain their own chemical weapons, the strategic value of an Israeli arsenal – current or potential – is clearly dubious.

The policy of ambiguity also deprives Israel of badly needed international goodwill. As Cohen highlights, had Israel ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention, it would have been able to participate in the recent strikes on Assad’s weapons facilities and be seen to defend the international norm that these weapons are beyond the pale.

Globally, there are fundamental changes to the nature of war and international security. Weapons of mass destruction are giving way to weapons of mass disruption, such as cyberattacks; conventional weapons are being transformed by semi- and fully autonomous weapons. The whole notion of deterrence is being challenged, and so is the military role of high technology.

In some ways, Israel is more than ready for this. It continues to live up to Ben Gurion’s vision that “science could compensate for what nature had denied”, rapidly developing capacity in robotic technologies, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. If this really is the path to security dominance in the 21st century, Israel may no longer have a need to maintain the rumours of limited and less efficient chemical weapons, and would do well to just put it all out in the open.

Perhaps the regional and domestic situation will at some point settle down sufficiently that Israel and its neighbours can start talking about making the Middle East a WMD-free zone. But until then, the question of whether Israel’s policy of ambiguity is more of a hindrance than a deterrent remains open.

This article by Teaching Fellow in Conflict Resolution and International Security, UCL was originally published at The Conversation.