Every great thinker is subject to misrepresentation. Yet, perhaps because the political traditions of the twentieth century are so close to our own, every great twentieth-century thinker is subject to a particular kind of misrepresentation.

This misrepresentation is a circus act in which the thinker is assessed by a political tradition and transformed into a political partisan for or against the causes of the hour. The ringleaders of this circus act wish the thinker to perform for their audience, inciting appropriate emotions of praise or indignation toward that thinker. In this circus act, Leo Strauss, who hardly wrote about the United States and never wrote on foreign policy, turned into a neoconservative bear to frighten those opposed to the Bush administration and the Iraq War.

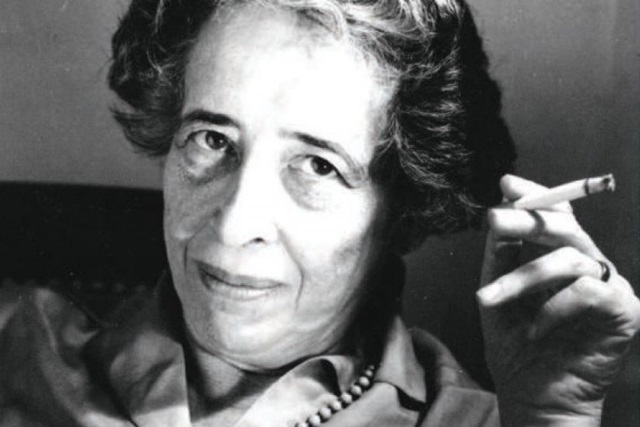

With Hannah Arendt, the circus act is rather different. Here, the circus ringleaders domesticate her to the political tradition of American liberalism, so that she can be brought out to cheer for liberal or progressive causes and galvanize resistance to the forces of reaction. Arendt, they assume, is on their side.

Following the political events of 2016, this circus act has become a regular feature in the flagship publications of liberalism. Within a month of the election, writers in The New York Review of Books invoked Arendt to oppose the impending inauguration. Keenly publicizing that Amazon had to restock Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism due to an increase of sales in early 2017, others use Arendt to draw readily applicable explanations for all of liberalism’s present bugbears, from the inability of left-liberalism to hold an effective political coalition, to the alt-right, to anti-Semitism, to sloganeering about the “banality of evil.” Activists all the way up to Chelsea Clinton do this. Turning Arendt’s profound phrase into a liberal cliché must dismay Arendt scholars; political theorist Corey Robin rebuked Clinton’s misuse of the phrase in a Twitter exchange, and the ensuing to-and-fro made it clear Clinton did not know what she was talking about.

These circus acts are premised on a fake character. Letting Arendt speak for herself recovers her intellectual independence, as someone who defined herself apart from and against the political traditions of her day, including progressive liberalism. Indeed, letting Arendt speak for herself recovers her status not as someone who wished to align with any political movement, but as one who consciously sought the status of a pariah.

Read the article by Nathan Pinkoski on MercatorNet.