In 1910, Harvard University Egyptologist George Andrew Reisner was conducting an excavation in the palace of King Ahab in Samaria. Once the first capital of the Biblical Kingdom of Israel, the adjoining village of Sebastia had been reduced to a backwater in Ottoman Palestine. There the American stumbled on an extraordinary discovery – more than 100 pottery fragments inscribed with Biblical Hebrew inscriptions dating from 850 to 750 BCE.

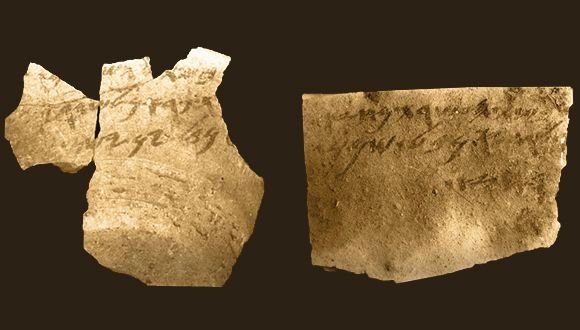

Called the “Samaria ostraca”, the broken clay pieces are today held in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums. Reading them was relatively straightforward. But what was their wider context in the ancient world and the Bible? What did they mean? Who wrote the inscriptions?

Archaeology was then in its infancy as a science. Unlike his 19th century predecessors, Reisner wasn’t an imperial grave robber intent on finding treasures to display in the British Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris or the Altes Museum in Berlin. But before William Foxwell Albright (1891-1971) revolutionised excavating in the Near East, and used this influence to advocate “Biblical archaeology” – in which the archaeologist’s task, according to fellow Biblical archaeologist William Dever, is seen as being “to illuminate, to understand, and, in their greatest excesses, to ‘prove’ the Bible,” – Reisner was operating in the dark.

With few texts preserved from 2,800 years ago, the ostraca are an invaluable resource. They detail place names, royal officials, receipts for commercial transactions and tax purposes, and taxpayers.

But despite a century of research, major aspects of the ostraca remained in dispute, including their precise geographical origins — either Samaria or its outlying villages – and the number of scribes involved in their composition. But a Tel Aviv University study published on 22nd January in PLOS ONE has found that just two writers were involved in composing 31 of the more than 100 inscriptions, and that the writers were contemporaneous, indicating that the inscriptions were written in the city of Samaria itself.

Read the article by Gil Zohar in Sight Magazine.