There is a persistent myth that European Jewry meekly acquiesced in their own annihilation during World War II. That iconic photograph of a Warsaw ghetto boy surrendering with his arms raised is remembered more than the context: the heroic but doomed ghetto uprising of April-May 1943.

The misconception that Jews were submissive or compliant was assisted by Zionist politicians in Israel during the early postwar years. They sought to distinguish European Jews from Israeli Jews: the former were physically weak and passive, and embodied the past; the latter, who fought for Israel’s independence, represented the strong wave of the future. The new arrivals were greeted with hostility or indifference. Some survivors were dismissed as sabnonikim (soaps), alluding to the soap Nazis allegedly made from the fat of incinerated corpses in the extermination camps.

In other countries to which they emigrated, Holocaust survivors remained silent, usually self-imposed, due to survivor guilt, the suppression of painful memories or simply a desire to assimilate quietly. Tales of resistance and heroism were rarely heard. When survivors were acknowledged, their resilience rather than resistance became the dominant Holocaust narrative. Footage of skeletal concentration camp survivors became embedded in the popular consciousness.

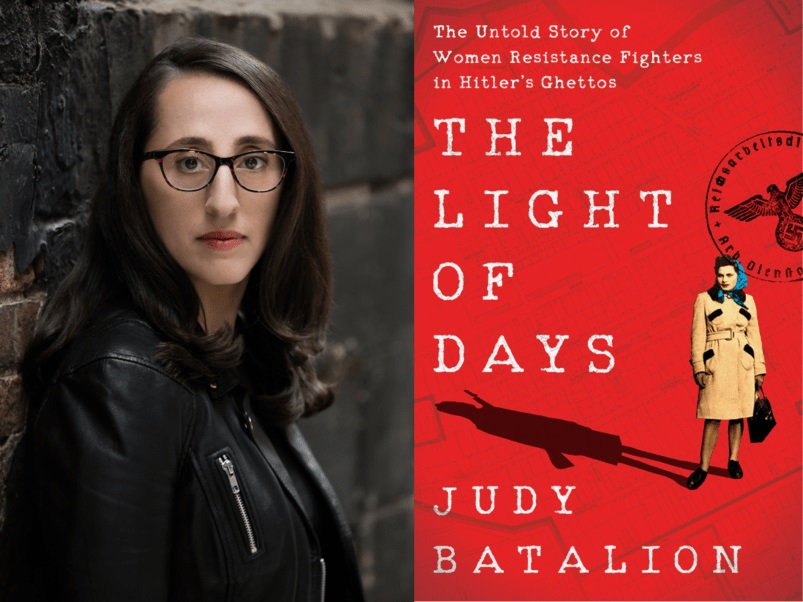

The Light of Days and X Troop rescue unknown stories of resistance from this historical amnesia. One focuses on young Jewish women in Poland who played an important role in opposing their oppressors; the other on German and Austrian Jewish refugees in England who became Britain’s secret shock troops of World War II. Both groups, fearless and courageous, were animated by a raw, defiant desire for revenge: to kill those who had extinguished their families, friends and former lives. Neither story has previously been told in such detail.

Read the article by Phillip Deery in The Sydney Morning Herald.