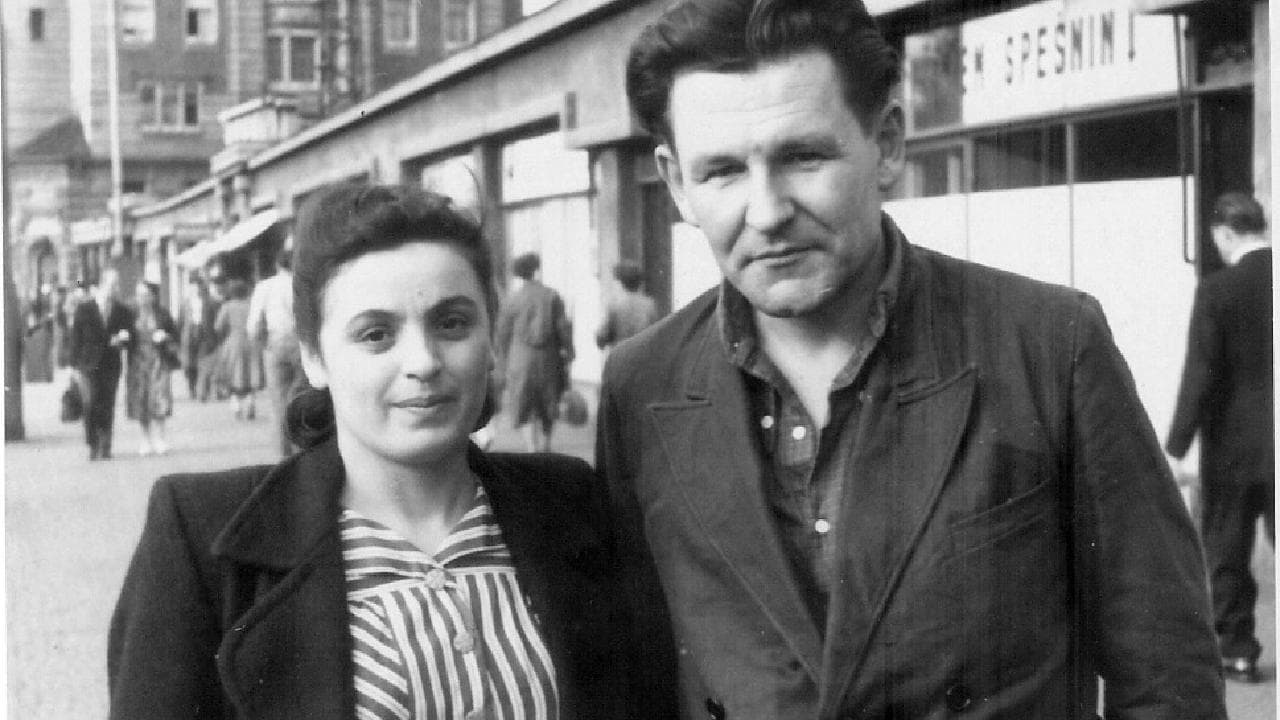

Heather Morris’s debut novel was a runaway success when it came out in January 2018. The Melbourne-based New Zealand writer wrote The Tattooist of Auschwitz after meeting and befriending the man, Lali Solokov, on whose story the book is based. It’s a love story: Solokov met his wife, Gita Furman, and fell for her, when, as a prisoner-functionary, he tattooed her number on her forearm.

In less than two years, that first book has sold three million copies around the world and the film rights have been bought. It has also been contested, by both Holocaust researchers and the family of the subjects.

The criticisms have been about facts, concepts, moods – all the factors that combine to instil historical understanding in a society – as well as the personal details of the key characters.

Why call Lali “Lale”, Sokolov’s son Gary complained, and why not take the trouble to get the number Furman had tattooed on her arm correct?

Wanda Witek-Malicka of the Auschwitz Memorial Research Centre, having studied the novel, said its errors created a “distorted version of Auschwitz” that was “dangerous and disrespectful” to its history.

Morris countered that the book was not “the” story of the Holocaust, but “a” story.

Now a sequel has been published: Cilka’s Journey, which follows the ensuing years of one of the secondary characters in the first book. Witek-Malicka called her story one of the most contentious sequences in The Tattooist of Auschwitz. Scholars have been on alert since the new book was announced.

Read the article by Miriam Cosic in The Australian.